Nicholas and Tonya, my salt-and-pepper set, on the Champs-Élysées in Paris

(forgive my scowl - you have no idea how hot it was that day)

On Sunday and all day Monday I felt that I should be posting something to commemorate Martin Luther King Day. I tried for something profound. I tried to be deep. I tried to be uplifting. I tried to create the second “I Have a Dream” speech. I tried to imagine a time when I had been discriminated against. But it all sounded so inauthentic and pompous. Who am I to make grand statements about discrimination and struggle after a week vacationing in New York City and then returning to my nice home in a lovely, tree-lined neighborhood where everyone walks their dogs to the local coffee shop?

And then I read a touching piece of writing by Bella on her blog One Sister’s Rant in response to a writing challenge on Beverly Diehl’s blog to talk racism. She learned at a young age what it meant to accept herself when she and her sister doused themselves in powder to lighten their skin. They got in trouble, but only to the extent that their mother was upset because they did not want to accept who they were. Their childlike reasoning concluded if they looked different they would be seen as better people.

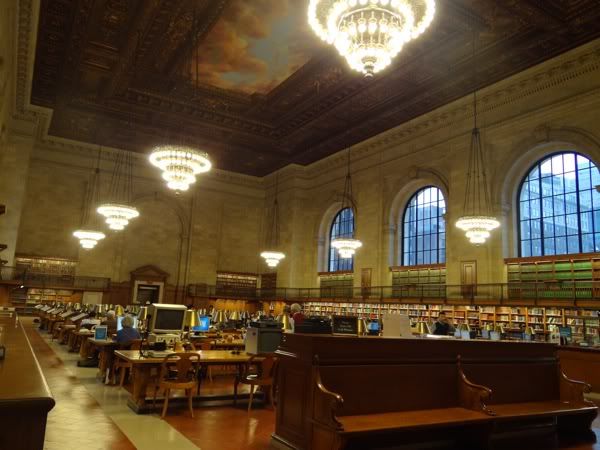

Her story reminded me of my own children when we brought them home from Russia in 1995. I called them “my little salt and pepper set” because my son is as fair as the Scandinavians across the Bay of Finland near his home city of St. Petersburg and my daughter is as dark as those in the ethnic regions of the former Soviet Union around the Black Sea. At 8 and 7 ½ years old, they had spent their entire lives in the narrow confines of the orphanage system in a very closed country. I had such fear that they would not be easily accepted because of their language issues or because they knew nothing about American culture except Flintstones cartoons. I worried that we would face a minefield of prejudices.

When my children arrived in their new home, they reacted badly toward the diverse ethnic groups in our corner of the city. They had never seen a black person before, although they had internalized the Russian disdain for non-white ethnicities. (You can read more about that country’s racism here and here.) That first summer when my son saw them – on our street, at the grocery store, in the park – he would, with no subtlety, point at them and make comments in Russian about their presence or appearance. Needless to say, I was mortified and made every effort to quiet him because I could tell by his tone if not his words that he was saying nothing good about them. I said a small prayer of thanks that no one could understand what he said.

That fall he began school in a classroom full of students who were Jewish, Irish Catholic, Indian, African-American, Asian, mixed race, and everything in between. Half of the students were children of university professors and the other half were on the free lunch program. Once he was settled in amidst this American melting pot, I never heard those comments again. Many of his friends have been and are the same African-Americans that repelled him at first. They saw him for the joyful presence he was and he saw beyond color to their humanity.

Nicholas and his cross-country teammate, Larry, after a hard race

(women pay hundreds of dollars for that hair color)

My daughter, on the other hand, directed her negative feelings only toward herself. She has the most perfect dark brown, almost black hair. Perfectly straight and thick. Her eyes are deep coffee and her skin a light olive tone. Yet when she was young all she wanted was blonde, wavy hair and fair skin like my sisters. She wanted to look like all the girls with Irish Catholic and German backgrounds that filled her classroom, that fill our town. As the mother, I was glad that her dark looks made it easy for us to distinguish her among all the blonde ponytails flying across the soccer field or basketball court. It’s also what made my husband and me sit up like a rocket and zero in on her when we first saw the video of orphanage kids that our adoption agency had sent us.

Yet she wanted nothing more than not to stand out. She knew her looks attracted attention – that she looked different – because people would stop me on the street and hand me their card just in case I ever wanted to start her on a modeling career. But at the beauty salon she kept trying to get our stylist to put blonde streaks in her hair. The stylist kept refusing, telling her she was not made to be blonde and she’d regret it later if she touched her perfect hair. Blonde didn’t match her lovely olive skin, she added.

Eventually, her desire to look like something other than herself faded as her interest in sports grew. Soon she was just another female high school athlete in soccer shorts and ponytail, with a headband made out of day-glo orange athletic tape. Two years ago, though, she had a chance to experience what life would have been like if she and her olive skin had never been a part of our family. She returned to her home city of St. Petersburg, Russia for a college semester abroad.

All around her she could see the treatment of non-whites in that country. She told us how much they hated the African immigrants or the Kazakhs or Chechnyans. Russia for Russians. She told us about the skinheads roaming the streets. And she told us that the Russians didn’t know what to do about her at first. She had the olive skin of those they hated, plus she spoke almost perfect Russian, which she used to help all her fellow students navigate the intricacies of life in that difficult country. Yet she had the visible confidence of an American, not a put-upon remnant of Soviet domination. Was she an ethnic Russian or was she American?

Mostly, she’s a survivor. She is fully herself. She wants to travel the world and has made friends from more countries than I have.

Tonya (#11), one dark ponytail amid a sea of blonde

Like any mother with children just slightly outside the norm, I fretted every day that they would face discrimination for being “different” or “other” because I ripped them from an insecure world and plopped them down into this comfortable, economically privileged, and, yes, rather closed culture of my own hometown (most important question – “Where’d you go to high school?” Tell me that and I can tell your life story). I’m blessed that they never needed a Martin Luther King to fight for their acceptance.

When we look at their experiences we see that hatred toward ourselves and hatred toward others can start at such a tender age. Embracing differences not only in others but also in ourselves can just as easily be taught. Although I’m sad my children had to feel what it was like to be an outsider in two countries, I’m proud that they never let that poison their spirits. And I repeat, as a mother I’m grateful every day that they escaped so much of the potential hurt and prejudice that attacks so many innocent children. Mine were lucky enough, as Dr. King had hoped, to be judged by the content of their character. Let’s hope we will all always be given that chance.

Have you ever worried that your children would face discrimination? Were you ever discriminated against as a child? Share your experience in the comments box. Then visit Beverly's blog to see links to the stories that others shared.

The garden at Château Chenoceau in the Loire Valley of France show us that

more colors make the garden a better place

![Grace [Eventually]: Thoughts on Faith](http://photo.goodreads.com/books/1166504427s/12542.jpg)